Currently reading

Negative Reviews and Me

We have Anne Rice to thank for the latest flap over negative reader reviews. The grandmother of all things paranormal waded into the author vs. reader cess-pool on the author’s end, publicizing her support for a petition to Amazon to force reviewers to post under their own name—her cure for the plague of “parasites” and “anti-author gangsters” who are “gratuitously destructive to the creative community.”

Instead of wasting time expounding why I think this is a horrible idea I’ll just refer you to K. J. Charles' terrific blog post, along with a hearty, “WHAT SHE SAID!” For those who haven’t read my earlier posts, suffice it to say that I am totally on the reader’s side of this conflict: reader reviews are a fact of life and assuming they don’t violate the law or the terms of service of the sites where they are posted, no one should have the right to dictate what counts as legitimate in other people’s reviews. (Credit goes to Debbie Spurts for this tidy formulation.)

That being said, I suppose it was inevitable after all the brouhaha (which I have contributed to with my own posts), that I would eventually train my finely-honed critical mind on my own reviewing practices, and take note of the irony that my personal policy has long been not to review books I hate.

I decided on this long before the current controversy, immediately after I joined Goodreads in the summer of 2012. From the beginning, I had two primary reasons for my policy. The first is that I almost never finish books I dislike and arguably it’s unfair to rate or review books I don’t finish. The other reason is Karma. Despite reading infinitely more than I write, I still think of myself as an author and I feel a camaraderie with authors’ struggles to write and publish and sell books. A lot of authors whose names I no longer remember helped me with advice and encouragement when I first published The Heartwood Box, and it just doesn’t sit well with me that I might go crap on their efforts. As I explain on my Goodreads author page: “Unless the book is very popular and my views won't make a difference, I avoid trashing stuff since I now appreciate how hard it is to publish a novel.”

I think my reasons are legitimate as far as they go, and other novelists I respect, including the great Heidi Cullinan, have argued forcefully that authors should be extremely cautious about what they say online, and especially avoid any kind of trashing. (Though for what it's worth, I have author friends I respect just as much who write extremely scathing, brutal reviews.)

But as I was researching material for my essay series, I came across a piece on the blog, Three Rs, “Why I Write Negative Reviews,” which included the following:

Thinking about it that way, those people who refuse to write negative reviews are real bastards, aren’t they? They’d rather let countless other customers be duped the same way they were than say an “unkind” word in a review.

I’ll admit that one stung. One of my most filthy, disreputable secrets is that I am a natural-born wuss who’s prone to panicking when I think I’ve hurt someone’s feelings. I speak from experience when I say this kind of personality trait can easily become a pathology. And no question, scathing reviews hurt. (I needed a few stiff drinks after an Amazon reviewer labeled The Heartwood Box “sleaze” and had to delete it from her Kindle due to its apparently unprecedented awfulness. Which, by the way, is emphatically not an invitation to my legions of rabid fans to go harass this reviewer.)

The problem is that none of my considerations has a thing to do with the books themselves or what I’m doing as a reader. I probably start 300 books a year, and finish roughly 250 of them, virtually all of them in erotic romance, specifically the subgenre M/M. I just posted my 200th review on Goodreads. Beyond the sheer amount of time and mental labor this represents, the simple fact is that I care about books, I care about this genre. Without indulging in grandiose notions of my own importance, I think it’s worth taking a little bit of time to figure out what I’m doing when I read and review.

Part of what impressed me with Three R’s essay and the blog itself is that the author has a very clear idea of what she’s doing when she reviews. As she says in her “About” section:

I think that readers today are too easy to please, and have been conned into believing that’s a virtue… We, collectively, need to raise our standards as consumers. Give me a little time, and I’ll show you what I mean.

She is understandably troubled by the disappearance of any kind of quality control or editorial standards that has been one of the consequences of the self-publishing revolutions, and is angry about authors who con readers with sock-puppets or glowing fake reviews.

I don’t agree with everything she writes. For one thing, I read M/M and erotica not YA, and the last thing I want is some Big Six publisher deciding what falls within the bounds of propriety or what is too risky or dirty. (Indies apply this pressure too, by the way, leading authors like Lisa Henry to self-publish or tone down their more risky offerings) And though I would always urge authors to painstakingly proofread their books, some of my favorite authors have lousy copyediting and I’ve just had to learn to live with it.

Most of all what I admire about Three R’s blog is that reading and reviewing for her is a thoughtful, active process. She has an agenda, not in the bad sense of a bias but in the good sense of a purpose. The word I would normally use for this sense of purpose and awareness is “critic,” though I mean it here to represent a mental attitude rather than some sort of professional credential.

Unfortunately for my wimpy nerves, it’s pretty hard to be a critic if you refuse to criticize. I’ve been putting boatloads of time into writing these blog pieces on erotica because I think the genre itself, not just specific books or authors, is important. It matters when it is misrepresented or misunderstood or undervalued. And I strongly believe that critical reviewing, including negative reviews, are essential if the genre is going to develop healthily. We need a community of thoughtful critics who take their roles seriously and are willing to do the hard work of developing critical concepts and standards for evaluation.

Whether I embark on a campaign of writing scathing reviews has yet to be decided, though I’m planning to bring it up with my therapist. Fortunately for my self-esteem, I have far fewer inhibitions writing about negative reviewing itself so stay tuned.

First Posted on my Blog: http://liliafordromance.blogspot.com/2014/03/negative-reviews-and-me.html

"…actions the author and reviewer could take to both clarify their expectations in the book review arena and provide meaningful remedies against wrongdoers..."

Nospin shared this link that sat wrong with me immediately. Okay, not the article which makes sense as well as being hilarious, just that the bit I quoted in the title was one of first things I read. Quoted by itself it is completely not what the article is about (a snarky sendup of ridiculous expectations worth reading for a chuckle).

Gee, how about authors can expect reviewers to legally obtain and not pirate books—the end.

How about "wrongdoers" get either shutdown by site support or turned over to appropriate law enforcement?

1

1

Review of A King's Ransom by Lia Black

Lia Black takes established fantasy tropes and crafts them into a smart, highly readable, sexy tale, with plenty of action and surprising touches along the way. Veyl especially is a new favorite character: I’m a city gal myself, so I’ve a soft spot for pampered creatures of civilization who are forced into situations requiring something called “camping” or, heaven help us, “roughing it” in that woefully misnamed entity, the “great outdoors.” (The scene where Kaidos orders Veyl to skin a dead animal was priceless.)

Black takes her time bringing these two together, with plenty of gay for you/out for you angst and lively love/hate banter. Both Kaidos and Veyl are more than they appear, and the book is full of unexpected moments of pathos and sweetness to offset the conflict and violence of the story. Those who have read Worthy know that Black writes wonderfully sensual, sizzling erotic scenes and King’s Ransom definitely does not disappoint.

That being said, it’s a long book at 150,000 words, and it would not have hurt the story to sacrifice some pages during the journey section, though in truth I was always engrossed reading it. With the arrival of Captain Engel at 40% with its kidnapping within a kidnapping and hints of a love triangle, the story becomes action-packed, with a small host of new characters (the wizard and his apprentice were particularly effective and moving), all racing towards a highly suspenseful and satisfying denouement.

Bottom Line: Lia Black writes a fun, sexy story that will satisfy fans of high fantasy and M/M. Highly Recommend.

1

1

Dream Casting for the Slave Catcher

[So inspired by someone else's Jesse Williams Post, I decided to reblog this piece of shameless self-promotion for my short story, The Slave Catcher. In the For What It's Worth column, I love when authors do Pinterest boards for their books, showing locations, characters, and anything that inspired them.]

One of the more fun parts of writing a story like this is finding images that seemed to capture the look of the characters. So I thought I would post a few. For more, please check out my Pinterest Board for The Slave Catcher:

First off, here is our narrator, Sam Beron, the Maradi PI.

Next we have Elia, born on Earth, and now bond to the Borathian, Raphael.

Finally, we have Liam, also of Earth, and bond to Zachariel.

The Slave Catcher is currently available on Amazon.

Here is the blurb:

Genre: Science Fiction, LGBT

16,000 words

Star City, best known for its brothels and casinos, is one of the few planets in the quadrant that outlaws slavery—for everyone, that is, except the galaxy bullies, the Borathians. Telepaths and recent conquerors of a backwards planet named Earth, the Borathians are simply too powerful to refuse. A special treaty allows them to bring their pleasure slaves or “bonds” onto the planet, and if one escapes, they have five days to recover him.

Sam Beron, private locator, may have been born on a Maradi space cruiser, but Star City is his home now and he’d say he despises slavery as much as any native. Unfortunately, a run of bad luck at the casino tables leaves him flat broke and scavenging expired military rations out of a neighboring dumpster. Next thing he knows, the Borathians are offering him a fortune to track down one of their escaped bonds, a beautiful Earth boy named Liam. What's a hungry locator to do?

Originally posted on my blog: http://liliafordromance.blogspot.com/2013/10/dream-casting-for-slave-catcher.html?zx=2c5c5865d3e6c06f

Review of Strain by Amelia Gormley

Terrific. I had my doubts about this because I’m not a zombie fan, and I considered the set up really risky. TV writers sometimes use the phrase “coinkydink” to refer to an overly convenient set of conditions, in this case a deadly virus that can only be cured (possibly) by having as much sex with as many people as possible. I’ve read a bunch of Evangeline Anderson stories with a similar idea—e.g. a demon who must have tons of oral sex with a woman or he’ll implode; a vampiric alien who must bite his severely needle-phobic lady-love or she’ll die of a virus—and they drove me bonkers.

But Gormley takes a basically implausible idea and uses it as a stepping stone for a consistently sensitive, intelligent exploration of sex, desire, trust, inhibition, power, shame—the list goes on. Given the essentially dub-con premise, the story is not as dark as I was expecting, but for once that was a plus, because Gormley avoids the exploitative potential in favor of a mellow pacing that really allows us to get to know and care about her characters—not just Rhys and Darius but a small crew of wonderful secondaries who create a very lived-in feel to the whole story.

There’s a fair amount of encounter-group style dialogue-as-therapy or narrated reflection, but the insights were so astute that again I didn’t mind at all. Examples.

“You made me do something I had to do but couldn’t. It’s like—“

“Like what?” Darius’ question was a hoarse whisper.

“Like shoving someone out the window of a burning building into a river far below.”

Darius could tell himself he was saving Rhys’s life all he wanted, but the fact was, he liked that power differential too much for it to ever be right.

“You can’t just go half in with a kid who doesn’t know how to play the game so that you have all of the authority and none of the responsibility.”

I’m pretty much a sucker for most D/s stories and dark fics, but I save my admiration for authors who go further than just tossing out some kinky acts for heat or shock value and actually explore the complex and contradictory impulses that underlie these sometimes unwelcome desires. That Gormley accomplishes such a nuanced, respectful exploration within the unlikely context of a Zombie Apocalypse is triply impressive. Highly Recommend.

Fantastic. I’ll admit to being nervous because I am emphatically not a fan of raunchy, R-rated American Frat comedies. There were moments, especially in the early chapters, when the authors skirted perilously close to cliché in the portrayal of Alpha Delta, but as we grow to understand, 90% of the problem is that the boys themselves have seen too many of those movies and seem intent on living up to their very questionable ideas of fun. But thanks to the authors’ overall self-consciousness, especially the clever allusions to Romeo and Juliet, the book deploys and then undermines the usual frat, excuse me Fraternity, clichés, creating a tender, insightful story about growing up, finding your place, and falling in love.

With Mark himself, the authors manage the almost miraculous balancing act of creating a character who struck me as being at once the epitome of the modern, disaffected teen and also wholly fresh and original. Crucial to this was the avoidance of the usual YA-friendly explanations for Mark’s behavior--a horrible step father, a neglectful mother, some early trauma--in favor something far more subtle and unexpected. Their restraint made Mark feel unusually real. In a lot of ways, Mark rebels because he doesn't have much to rebel against. He aggressively redefines his world to fit his need to lash out. This is a quality that we and Deacon discover gradually over time through dozens of small touches, instead of having it shoved down our throats in some tearful monologue.

All of this is good, but what made the book truly a pleasure to read was the writing. Though all of their books have been terrific, I think the Rock/Henry collaboration really comes into its own in Mark Cooper versus America. The narration is tight and energetic and perfectly infused with the highly distinctive idiom and mentality of its two MCs. I marked dozens of memorable, witty passages and phrases that just made me happy in the way that only terrific writing can:

The fraternity thing was just the latest idea out of Jim’s Top One Hundred Ways to Get Mark a Friend or Die Trying. Copyright Jim, 2013.

Angry bunny.

The guy, drunk, stumbled and went face-first into a bale of hay.

Everyone cheered. It was that sort of party.

At what point in your life did you decide you were the sort of guy who wanted to be fisted?

And then there were the moments of insight that made me know and care about these characters:

It was fine to be mocked or disliked on his own terms. But his sexual orientation was such a naked target, unfortified by nonchalance and lacking the benefit of being a persona he’d constructed. Gay Mark wasn’t sheddable like Smart-Ass Mark or Bitter-About-the-Move Mark.

Deacon smiled. He was pretty sure he was just the latest in a long line of people who had no idea what Mark Cooper was thinking.

Given that in many ways this book is the “Mark Circus,” I was gratified that I found Deacon as rich and compelling a character in his quieter way. Part of the strength of the book is that neither Deacon nor Mark could be fully realized without the other. Only Deacon recognizes the vulnerable young man beneath Mark’s smart-ass demeanor. On the flip side, Mark enables Deacon to cut loose and actually have fun. On a deeper level, Deacon is someone who needs to take care of others, and with Mark he’s finally able to do so in a way that is mutual and fulfilling instead of draining and self-sacrificing.

Perhaps the most unexpected thought I had reading the book was that this was the best YA novel I’ve read in ages. That reaction created a mini-existential crisis because a rebellious part of me, the part who remembers what it was like to be a teenager, really wants to make the argument for why this book is healthier, truer, and just plain better than most of the crap directed at teens. Depressingly, the more conventional, timid, mother-of-a-teen part of me is not quite ready to recommend a book which heavily features fisting and other kink for the under twenty crowd. My hesitations feel all the more craven and pathetic given that I know for a fact (yes I do know how to check the google search history) that my son and his friends already watch really explicit, rasty stuff online.

I won’t solve this today, but if anyone reading this decides to nominate this book for YA Book of the Year, you have my vote. In the meantime enjoy Mark et al. You’re in for a real treat.

2

2

Review of Bad Idea by Damon Suede

We have the gift of bullshit

This is a very long, very ambitious book. The surreal zombie-road-race-in-Central-Park opening sets the overall tone. Borrowing from the theme, we might call it a comi-con in miniature, a collection of disparate themes and genres that come together in a mind-bogglingly creative synergy: it’s an M/M romance, a study of gay life in Manhattan (something very, very different), an exploration of the creative process, inspiration, and collaboration, a loving tribute to a particular corner of pop culture, and when taken altogether, a larger statement on uniquely American and modern forms of cultural expression.

We are given a taste of Suede's ambitions in his dorktastic tour de force of a second date--to see Catwoman at the Chelsea Clearview. Silas, proudly dressed as He-Man, declaims:

Pop culture. Nobody does bullshit better than us. Right? China took over manufacturing. And the Middle East has us on fossil fuels. That’s just geography and politics. We’re a nation of whacko immigrants. Scavengers and con men. We crossed the ocean on faith, stole some land, and then stone-cold made up a whole country out of nothing but balls and bullshit.

Silas' insights here are good examples of a pattern of what we might call self-conscious ambitiousness: They invite a level of meta-analysis as to Suede’s larger ideas about pop-culture and creativity, both for the comi-con world of superheroes, comics, artists, suits, and fans, and (by implication) Suede’s own pop-culture niche (embodied by the character Rina) of romance writers, publishers, readers, and booksellers.

As you enter the novel’s world, the sheer length—three times the average long romance—warns you that Suede is not content to follow any set generic expectations. He will take his time; he will give you the details. Silas and Trip’s relationship develops slowly, over multiple dates, with fumbles, insecurities, and inner to-text-or-not-to-text debates. Far more than most romances, the book takes seriously the fact that most people do actual work, in the pursuit of real-world careers, in this case comic book illustration and F/X make-up. I found those details endlessly fascinating and satisfying.

Most riveting, the book both explores and dramatizes the creative process, beginning with that first inspiring idea, through the exhilarating and frustrating struggles of execution and collaboration, all the way to the gut-wrenching process of bringing a work public.

Spoiler Alert: This genre is not short on sob stories and hurt-comfort angst fests, but for sheer psychic pain, it’s hard to match Suede’s picture of Trip’s brush with artistic self-destruction. How many “Scratches” are there sitting in boxes in some basement, testament not to the failure of imagination or talent, but of ability to deal with the terror and humiliations that are inevitable parts of going public with your work? I was most struck—most floored—by Suede’s insight that sometimes the people who love you the most, who most want to help, unwittingly sabotage that all-important final step with their encouragement and pressure. Spoiler Over

Oddly, given the book’s attention to comics and F/X, I found the style itself owed most to theater. In some ways this was great, because there’s a memorable, sparkling quality to most of the dialogue. My GR status log and kindle edition are full of highlighted quotes I found brilliant and insightful. However, Bad Idea makes for a very, very long play. While we are accustomed to that epigrammatic style and speechifying rhythm on stage, it often feels downright unnatural in a novel. The theatrical quality seemed if anything to intensify in the last 20%, which was a problem because as the emotions become more intense, the characters become ever more articulate, popping out with pithy aperçus like “Never make a permanent mistake to solve a temporary problem,” or “If you love life, life will love you back.” Scenes between Rina and Silas, Trip and Cliff, Trip and Kurt, and (my least favorite in the book) Trip and Max could be transposed with little loss for the stage, and especially the scene with Max are overlaid with the kind of emphatic symbolic signifying that we expect in a play, but can feel fake or overwrought in a novel.

It feels churlish and a bit ridiculous to complain that a book is too brilliant, especially one that is as full of ideas and insights as this one. I am in awe of what Suede has accomplished here, and I think it bodes incredibly well for this genre that we have a writer this talented, dare I say this major, who has produced a book like this: one that pushes the boundaries of the genre even as it explores with incredible depth and insight that inimitable American gift of bullshit that is our pop culture.

Cross posted on my blog: http://liliafordromance.blogspot.com/2014/02/goodreads-reviews-bad-idea-by-damon.html

2

2

Why is it so hard to review smut?

(This is the fourth essay in a series that argues for considering erotic romance as an "emerging genre," and explores how the genre connects to the larger changes currently roiling the publishing world.)

My last essay in this series took some easy pot shots at two-year-old reviews of a book I don’t want to review myself since that would mean I’d feel obligated to reread it.

Confession’s good for the soul and all that. Now that’s off my chest, excuse me as I load up for my next round of shots.

I’ll make one claim for Fifty Shades of Grey. The book was important. That’s why critics were writing about it in the first place. The book was never important because it was 2012’s answer to Ulysses, but because it represented a confluence of trends that had been going on under the radar for several years, and got shoved into the wider public consciousness by the book’s stupendous sales.

What trends were those? Well, thank you for asking. I’ll name four: the rise of self- and indie- publishing, their rapidly increasing share of total book sales, the growing popularity of erotica, the new importance of non-traditional routes to publication such as pulled-to-publish fan fiction.

In effect, the reviews I looked at were protests against the book’s importance. They drip with annoyance that a piece of hack fiction, only liked by stupid, undiscerning people, could sell this many copies. Worse, thanks to those absurd sales, FSoG actually garnered reviews in prestigious journals by smart critics who should not have to write about stupid trash. Perhaps running under the surface for some critics was the recognition that self-published garbage, far from being recognized as the joke it should be, is instead garnering a larger share of the sales pie every year and in doing so is disrupting the economics of the part of the publishing world responsible for producing actual good books.

I get it and I really do sympathize. A lot of people who adore erotica and had been reading it for years were horrified that Fifty Shades of Grey became the defining text of the genre. The sales don’t make any sense under any system of justice or merit, and personally I'm jealous as hell. After all, my own erotic masterpiece, The Heartwood Box (currently on sale at Amazon for 2.99!!!!) inexplicably has not sold nearly as well as Fifty Shades of Grey! Even though I THINK IT’S JUST AS GOOD! Like, just check out the bodacious cover:

Shameless self-promotion aside, the critics I was taking on read and review some of the best contemporary writers of our age. It is hard to spend a career watching extremely talented authors struggle to find an audience, while a book you consider a total POS becomes one of the best selling books of the decade. To add insult to injury, these critics must be aware that their own reviews are only fueling this infuriating “phenomenon.”

Ultimately, I think we’re better off looking to Malcolm Gladwell for answers on the phenomenon of FSoG than to the book itself. Critics’ anger over that phenomenon is understandable, but it’s also petty and represented a disgraceful failure of imagination and critical engagement. (For an example of what I mean by “critical engagement,” see Emily Eakin’s review in The New York Review of Books, which gives an excellent analysis of the book’s status as fan fiction while avoiding the hostility and condescension that most critics indulged in.)

For the umpteenth time, the reason I’m writing this, the reason I think it’s important, is that FSoG is only the most well-known example of what I am calling an “emerging genre.” Almost by definition, emerging genres have trouble in their early days with mainstream criticism. I would also posit that new genres like hip-hop or erotica which deal with particularly fraught parts of our culture such as race, sexuality, or gender will always pose greater problems with reception. If we are going to get past these barriers to what I think would be a true critical engagement with erotica, we need to get out in the open the reasons why erotica poses such problems even for very smart critics.

The first and obvious answer is sex, though I have to say that with qualifications. The reviewers I targeted in my last piece were all liberal intellectuals who would be the first to denounce religious or traditional injunctions against sexual freedom and sexual pleasure. Still, as everyone in the galaxy knows, FSoG isn’t just graphic, it’s kinky, with all that BDSM stuff, the Red Room of Pain, spankings, and those silver bead thingies! Critics’ responses to this aspect divided. Some (probably more honest) critics were horrified by the political implications of BDSM and just denounced it. Those who didn’t want to come off as uptight tried to play it cool, adopting a tone of knowing mockery and comfort with kinkery.

I find the latter attitude especially unfortunate, because in truth there is nothing simple or comfortable about BDSM erotica. We are talking about a very fraught area of human desire, and material that is at the very least politically problematic when it’s not downright disturbing and objectionable. I am suspicious of those who claim to be blasé about depictions of BDSM, especially when it’s obvious (as it was with every mainstream critic that I surveyed) that the critic is totally unfamiliar with the erotic romance genre. (And just to be clear: BDSM erotica has little or nothing to do with real-world BDSM; this cannot be reiterated often enough).

That is not to say that I am satisfied with the kneejerk condemnation typical of many feminists. Whether we love BDSM erotica or find it offensive, making sense of our reactions to it requires a lot of hard thinking about our fantasy life. Why are some women so turned on by submission or rape fantasies? For those who are appalled by them, what are their fantasies like and why might they be so different? What is the moral status of our fantasies? To what extent do private sexual fantasies actually impact the “real world”? What does it mean when our fantasies oppose our moral values? Is there anything we can or should do about it? Is it acceptable to sit in judgment on, condemn, or mock other people’s fantasies?

These types of questions are not the usual domain of literary criticism, but I think such introspection is necessary if we are going to engage on any meaningful level with erotica. What we got instead was a nearly hysterical attack on E. L. James’ prose. Katie Roiphe discerned intimations of the apocalypse in women’s willingness to tolerate it, and Salman Rushdie needed only two pages to conclude, "I've never read anything so badly written that got published. It made 'Twilight' look like 'War and Peace.'"

Now, for anyone who reads a lot of self-published erotica that’s just crazy talk. It’s not a myth: plenty of self-published writers don’t know basic grammar. I speak from experience when I say reading them feels a lot like reading essays from the bottom third of the grade pool in a freshman comp class. Fifty Shades of Grey drastically needed cutting, but the worst that can be said about the prose is that it’s mostly pedestrian with occasional flourishes of cleverness. The idea that it is egregiously worse than a lot of genre fiction is just silly. I have my own pretty severe problems with it, but I’d still rather reread the whole trilogy twice than read anything by Nora Roberts, Danielle Steele, Dan Brown, or Nicholas Sparks.

I suspect that a lot the aggressive trashing of the prose style served as a helpful cover for less permissible anxiety about the book’s depiction of sex. But I also think it reflects the assumption by most critics that “good book” equals “literary.” At earlier points in my life I would have passionately agreed with that, but nowadays I find it rather quaint and Arnoldian. I don’t find it a helpful standard for dealing with erotica or any other example of genre fiction. There are some erotica writers capable of gorgeous or stylish prose (Alexis Hall and Harper Fox to name two), and some readers who are really appreciative of those qualities, but the majority of authors and readers are mostly focused on other, ahem, values. I hope to deal in a later essay with some of the different values we might look for, and also how readers, fans and critics go about working out standards of quality for an emerging genre like erotica.

Ultimately, the most striking aspect of the mainstream reaction to FSoG was the sheer amount of hostility it aroused, which raises the question why? Why get so angry? Why so much hysteria over the book’s style? It’s not like the US is experiencing a deficit in trashy, poorly written books or TV shows. American men spend millions of hours watching online porn, and yet it does not arouse anything like this outrage among mainstream cultural critics, despite its quite questionable cinematic quality. Are bad wank-reads really so much worse than bad porno videos?

And here I think the answer is depressingly straightforward: the readers were women. When the news hit that all those bland-looking Kindles were actually hiding some pretty explicit smut, people who should know better suddenly began ravening about horrible writing, morality, and the dangers of Cinderella complexes, as if the average woman you know isn’t capable of deciding what turns her on or distinguishing between a juicy one-handed read and War and Peace. Think about it: there is simply no way mainstream cultural critics for organs like The New York Times or Newsweek would have written with such condescension or hostility about FSoG if the target audience had been, say, Gay or African American or working class.

I will close by reiterating a point I have made elsewhere: there is absolutely nothing new in efforts to police popular forms mostly enjoyed by women. Before my career writing smut, I was a scholar of 18th and 19th century English fiction. For almost all of its history, the novel has been the major popular form written and consumed mostly by women. And at every stage of that history, we have seen efforts by critics to use canons of taste, artistry, and morality to dismiss the genre and the women who enjoy it.

Critics, parents, and clerics throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth century worried obsessively about teenaged girls’ love of novels. Romances were blamed for the decline in morality and virtue, and critics didn’t hesitate to prognosticate the end of marriages, families, and civilization itself because of women’s propensity to indulge in dangerous fantasies promoted by novels. (I admit to experiencing a certain giddy elation at the sight of a gadfly critic like Katie Roiphe taking on the role of the 18th century cleric thundering about the apocalyptic implications of trashy female reading.)

Cultural paranoia about female fantasy is so persistent and reappears in so many guises it's hard not to suspect it is some inherent part of our species, better explained by anthropologists or psychologists than historians. Interesting as I consider this point, you will have to go off to academia to find a really adequate treatment of it. I no longer frequent that establishment, thank goodness, so instead of perusing social science journals, I think I’ll reread Concubine of a Space Conqueror! Elliot, the hero of that little gem, possesses the unshakeable conviction that sex with him will be scorching enough to distract his glowering alien lover from invading Planet Earth. More power to him.

(First published on my blog: http://liliafordromance.blogspot.com/2014/03/why-is-it-so-hard-to-review-smut.html)

Every now and then I read something that reminds me that M/M romance and gay erotica are seriously different genres. I dislike essentialist sounding explanations, but there are times, (most often after I've spent more than four and a half minutes watching pornography) when I just feel like shouting out: men and women are turned on by very different kinds of stories!

I enjoyed reading these stories--they are well-written and inventive--but I liked them more because they gave me a window into a world that felt truly exotic and weird than because I felt they got at the heart of my own experience. (The only chapter I can say that about was David Stein’s smart and incisive Editor's Note, “Value-Added Porn,” on the difference between porn and erotica, which I plan on quoting in some blog post if I ever get my act together.)

For me, the world of the stories was interesting but not appealing. It wasn't just the dog bowls and the piss play. I found the mentality of the slaves impossible to identify with.

"I felt full and complete being used by this totally hot stud, used like the dog slave I am, used to bring him pleasure."

"Worshipping men like him and my Master is why I was born."

“My pain or pleasure wasn’t important. All that mattered was serving him.”

That level of abjection and selflessness is just too much for me. I find it alienating. However, I think my distaste is exactly that, a matter of taste: I don’t usually like most “Club” novels that purport to depict people in the BDSM lifestyle. Any story in which characters eagerly adopt an established role leaves out most of the inner conflict and ambivalence that is the most erotically charged part of D/s for me. (As slave fics go, I find Yaelen’s inner torments over his attraction to his master? lover? rapist? both fascinating and intensely erotic, though in other ways Bloodraven is far too brutally sadistic for my taste).

The genre of Winner Takes All: Master/Slave Fantasies by Christopher Pierce doesn’t help matters. With a few notable exceptions, the book offers erotic teases, ficlets, which are little more than a hot scenario or exchange in a fantasy version of gay slave life. Some stories are better than others--hotter than others--but there was not enough characterization or complexity for them to truly be erotic for me. Every character in this collection is essentially interchangeable and virtually all of them wholeheartedly embrace their situation. And that I think is the key difference. It's not enough that a book describes a kinky scenario; unless I feel involved with the characters, and to some extent challenged by what they are experiencing, then it's not very different than watching porn or looking at explicit photos, neither of which I find particularly arousing.

There were a few exceptions: I really admired "The Executioner's Boy.” It was imaginative and moody and dark. It also surprised me: usually I can't tolerate any erotic fiction that includes serious threats of death as part of the domination, but this one made that work. The title story, the last in the collection, was the longest and the most developed, with a strong story arc and compelling character development, though the narrator’s personality or mentality didn’t differ noticeably from that of the slaves in the other stories.

As I said above, I was very interested reading this. In some instances, you can learn more about yourself—your imagination and your desires--from well-written fictions that don’t quite work for you than from ones that fit your kinks dead-on. I suspect that M/M romance will always have a somewhat uneasy relationship with gay erotica and speaking from the M/M camp, I think it’s worthwhile to be both aware and respectful of how these genres—and their authors and audiences--differ. There’s no question that these stories are arousing for the right audience, and echoing editor David Stein, I am firmly of the opinion that such fiction has value—drastically underrated value. I admire Pierce for his achievement, even when I can’t totally experience it as it was intended.

1

1

2

2

Loved it. I understand people's hesitations with the subject matter, but I thought the author handled them beautifully--with respect and compassion and a great deal of subtle insight. Though I did cry, I did not find the book overly sentimental at all. Understandably, there is not much in the way of irony to offset the sweet or emotional elements, but for once instead of being manipulative or cheap, I found those elements deeply true to the story--in fact, though I'm sort of shocked to be saying this, I found that the sentimental aspects of this book were those that most challenged me.

Ethan's mother describes his world as black and white." I would probably use the word "literal"--subtle or inferred meanings, sarcasm, nuances, things outside his own experience are almost impossible for Ethan to understand. There is definitely an innocence to him, and he requires help and reassurance with tasks that most adults perform independently. It's understandable to feel conflicted about Ethan's relationships because these are qualities that we often describe as "childlike" (though in my own experience few if any children are actually like that at all unless they have special circumstances like Ethan's). In any case, I really appreciated how the book forced me to think through the problems with applying the word "childlike" to Ethan. Our discomfort is real but also needed to be faced: as his mother says, Ethan is an adult male, with adult urges. Denying him this central and joyful part of human experience just feels wrong, especially since Ethan's own desires are very strong. Too many other things were taken away from him because of his injuries. I think the author made a good choice having Ethan be 18 when he was hurt. Judging from his family's attitudes and Ethan's own confidence, it's a safe guess that he was already sexually active "Before." There are clearly risks to sexual activity since he can be taken advantage of and he has trouble remembering the rules of appropriate behavior, but I think his parents were right to treat his sexuality like they do his troubles washing his hair or finding a job that works for him--as part of the process of his carving out a new life for himself after his injuries.

I was really impressed with how Loveless handled the family part. Obviously, his parents are two very admirable people, but they did not feel unreasonably wishful to me--maybe the better word was hopeful. They're hippies to begin with and they've had ten years to come to terms with what happened to their son. She also avoided the tendency to hyper-articulate, therapeutic monologuing that too often accompanies stories where characters are recovering from traumatic events; those speeches too often cross the line into moralizing and they always kill the realism for me. If Liz and Nolan sounded a little pat when discussing Ethan's situation, it makes sense since they've obviously had to explain it many times.

That leaves Carter, who was trickiest, but I thought Loveless totally succeeded in making me understand and accept his choices. I've read several other books in the last year where the MC's occupy what I'll call radically different mental spaces (Glitterland and Muscling Through, to name two), and to my surprise, I found Ethan and Carter's relationship made the most sense to me. There was something very complementary in their challenges. Ethan has real limitations but thanks to his personality he is able to push through them to the greatest extent possible. Carter is the exact opposite: far more than any physical problem, his emotional response to his condition is what cripples him. He desperately needs acceptance; Ethan comes as close as is humanly possible to offering Carter a life where his Tourette's is simply a non-issue. Though Carter might have to take care of Ethan in more ways than is usual, in exchange Ethan can give Carter a much fuller existence than he has been able to have so far. (I'd just add it's easy to forget the myriad private ways spouses and lovers take care of each other. People can be far more dysfunctional than their friends realize--unable to take a shower or eat or leave the house, and they depend on their partners to help them through it.)

Like the timing of Ethan's catastrophe, I think it made a big difference to my acceptance that Carter is so isolated. Almost the entire context for his relationship with Ethan is provided by Ethan's family and friends, who are understandably encouraging. Ethan already has a place with them, and it makes sense that they would easily accept Carter's differences. Ethan obviously does much better with people who are familiar with him and his quirks. It's easy to imagine it being a disaster if Ethan had been thrown into uncontrolled situations with people he didn't know--and without really knowing Ethan and seeing the nuances of his situation (in other words, by reading this book) most people wouldn't be able to accept his relationship with Carter. As things stood, Carter only had to win over Alice, who like Ethan's family has strong reasons for wanting Carter to find love and happiness.

I'm probably not focusing enough on the downsides to it, and I honestly can't imagine being in a relationship like this myself, but the issues did not trouble me while I was reading. I'm enough of a romantic to cleave to the idea that true love comes in a multitude of forms, and I'm deeply grateful to Ryan Loveless for creating such an unusual and beautiful example here.

3

3

I had an uneven response to this. I think McKenna is one of the best military writers I've come across. Her knowledge of the details, speech patterns, attitudes of US soldiers struck me as spot on, and infinitely better than the average writer. I really like the story's premise and the way that the book focused on integrating werewolves into combat operations in real-world "theaters of war."

That being said, this is a long book, and yet I felt like there were some key aspects missing. We are never given any specifics or history about werewolves' open role in this society or in the military and since I was very curious about it, I ended up feeling severely frustrated, especially since what we do get tends to be reiterations of the same basic situations over and over again.

Bottom line: I admired the writing here tremendously, so much that I'd even posit that McKenna should be required reading for anyone thinking about writing about the US military. Beyond that, I had a lot of frustrations with what the story included and what it left out.

2

2

Favorite Reads of 2013

Originally posted on my blog:

It’s that listy time of year again! So first off, I’m exuberantly proud to say that as of 12/20/13 I have, according to Goodreads, read 245 books. That number does not count rereads which probably amount to another 100, nor does it count the 43 books I started but didn’t finish. Virtually every book was some variation of M/M.

The following, rather eccentric list is exactly what the title says, my favorites: not the books I thought were best, but the books that I enjoyed the most, that I reread most often, and that for whatever reason became orientation points for me—books that I reflexively compare other books to. They were not all published this year. I've reviewed most of them on Goodreads. Click my Favorite Reads 2013 shelf to find the reviews.

So here it goes.

Favorite Sci-fi:

Claimings, Tales, and Other Alien Artifacts, by Lyn Gala

Bone Rider, by J. Fally

Favorite Fantasy:

Kei’s Gift, by Ann Somerville

The God Eaters, by Jesse Hajicek

The Magpie Lord, by K. J. Charles

Richochet, by Xanthe

Favorite Hot Reads:

Collision Course, by K. A. Mitchell

Bad Boyfriend, K. A. Mitchell

Dirty Laundry, by Heidi Cullinen

Not His Kiss to Take, by Finn Marlowe

Favorite Feel Good Reads:

Physical Therapy, by Z. A. Maxfield

The Trouble with Angel, by J. M. Cartwright

Stroke Rate, by L. M. Sotherton

Favorite Dark Reads:

Gamble Everything, by Cari Waites

Last Rebellion, by Lisa Henry

Mind Fuck, by Manna Francis

Favorite Graphic Work:

Maiden Rose, by Fusanosuke Inariya

Favorite Tentacles:

Gay Tentacles From Space, by Charlotte Mistry (also Favorite Title)

Mating Season, by Kari Gregg (in Bump in the Night, ed. Heidi Belleau)

Favorites From the M/M Romance Group's Love Has No Boundaries Collection:

When You Were Pixels, by Julio-Alexei Genao

The Lodestar of Ys, by Amy Rae Durreson

Worthy, by Lia Black

Most Read Author:

Keegan Kennedy (also filthiest, craziest, most holy-shit-I-can't-believe-I-just-read-that) See Cops and Robbers for a good example of his work

Favorite (and perhaps only?) Book with No Sex:

The Foxhole Court, by Nora Sakavic

Best of the Best:

If I had to pick one book from this list that represented my absolute top pick for the year, it would be Claimings, Tales, and Other Alien Artifacts by Lyn Gala. I’ve lost count of how many times I’ve reread it now, probably because it represents the perfect fusion of my two favorite genres, M/M and sci-fi. Click here for my very inadequate review on Goodreads, but really just read it.

Supplemental Notes:

As of this writing, The God Eaters, The Foxhole Court, The Last Rebellion, Not His Kiss To Take and all the stories from Love Has No Boundaries can be downloaded for free--just click the title's link. Maiden Rose can also be read for free online.

I'd also like to reissue the warning I posted last February. Every single one of these books is M/M, and except for the last, they are all ADULT ONLY. Several, and not just the dark reads, feature BDSM, rape, and/or non-consensual situations. It is crucial to know your own limits and pay attention to content warnings. Always feel free to ask me if have any questions or worries about this. I truly believe reading in this genre should be about pleasure, not about testing your triggers or restocking your supply of nightmare-fodder.

And in Conclusion:

I'd like to say a few thanks yous: first to Goodreads. Despite all the turmoil this past fall, the site remains the primary incubator for the M/M genre, bringing together authors and readers in endlessly productive and creative ways. My next thank you goes to my Goodreads friends for all the work they put into discovering, reading, and reviewing this emerging genre, and enabling me to discover authors I'd never know about otherwise. And finally, I'd like to thank the authors themselves for being so talented, for choosing to write in this genre, for writing such intelligent, enjoyable, and challenging books, and finally for getting their work out there so I could find it. Hopefully this post will help you find it too.

There are a lot of amazing books coming next year--I am already looking forward to sharing them with you in another post a year from now. In the meantime Happy Reading and Happy New Year.

Fifty Shades of Boneheaded or WTF is Wrong with Erotica Reviewing?

So this summer, one of those dear, article-sending friends we all have, knowing of my interest in erotica, forwarded me a review from The New Republic of Alicia Nutting's novel, Tampa, entitled, “The Phony Transgressiveness of Tampa” which caused a bit of a personal kerfuffle. Here is the author, Maggie Shipstead’s, opening paragraph:

What makes a piece of fiction erotica? I’d say that erotic fiction is defined by explicit sexual content included for its own sake (not necessarily in service of a story) and an intent to arouse. Since as far back as John Cleland’s Fanny Hill: Or, Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure (published in England in 1748), erotic fiction has tended to have a cyclical, masturbation-friendly structure. Flimsy, ostensibly plot-advancing sequences segue into sexual encounters much in the way pizza deliveries and doctor appointments perfunctorily frame pornographic movies, providing a bit of context and loosely situating the observed participants.

Shipstead then goes on to muse about books by Philip Roth or Nabokov that “transcend” the genre with their stunning literary style, and conclusively demonstrates why Tampa fails to do that.

I spent several hours composing a comment, which I imagined was so magisterial it would generate lots of responses and debate. Ha Ha. Anyway, not able to let its stupendous brilliance rest in obscurity, I will reprint it here:

Obviously Shipstead is perfectly free to define “erotica” using the same criteria usually used for pornography. However, for those who actually read and write in this genre, “erotica” is fully a subgenre of romance, but without the old publishers’ injunctions against explicit terms and descriptions. Shipstead’s general dismissiveness towards the genre is only reinforced by her use of Lolita, one of the most acclaimed novels of the twentieth-century, as her standard. I heartily concede most erotica published (at any time in history) does not “transcend” the genre like Nabokov’s masterpiece does. But could we find a more loaded comparison? Do we usually evaluate Tom Clancy novels by the same standards as Joseph Conrad’s? Romance, erotic or not, is genre fiction, just like thrillers, mysteries, or sword-and-sorcery novels. It’s not trying to transcend anything, but that does not make it the same as pornography in either content or purpose.

Based on Shipstead’s review and the blurb, I would characterize Tampa (like American Psycho) completely as satire, specifically of the most aggressive Swiftian mode that pulls readers in with its shocking material in order to leave them feeling compromised and implicated. Any arousal you feel reading Tampa is designed to make you feel guilty and filthy, which is a legitimate authorial goal, but could not be further from the governing logic of romance, no matter how much sex is depicted.

Obviously, erotica is supposed to be hot, but it’s about fantasy and wish-fulfillment and cutting loose your inhibitions. Above all it’s about pleasure. Sometimes that pleasure can feel quite transgressive, or at least forbidden, but most romance writers and readers would agree that the sole unifying convention of romance is the Happily Ever After (HEA). The HEA almost by definition precludes a story featuring a sociopathic pedophile as its heroine. For those interested in reading books that show more of the range of erotica today, I would recommend the hilarious and intelligent Control by Charlotte Stein or Out of the Woods by Syd McGinley (click here for my review), a genuinely transgressive and sometimes disturbing book, but one that ultimately falls within the conventions of romance.

Rereading my comment now, I don’t find it particularly harsh, but I fully admit to being in a full-on conniption when I wrote it. Shipstead’s piece raised some bad memories from the “reviews” of Fifty Shades of Grey (FSOG) that journals like the New York Times and Newsweek felt obliged to publish when the trilogy sold 70 MILLION EFFING COPIES. Needless to say, major journals that cover culture do not usually review romance, but I was still pretty appalled at what they managed to say about the book. Here is a run-down of what I see as the main problems.

1. Endless condescension towards people (the vast majority of whom are women) who liked the book, commonly epitomized by references to mothers—mommy-porn, mom-friendly, etc. Here is a typical quote from an early piece on the “phenomenon” from the Times:

“Fifty Shades of Grey,” an erotic novel by an obscure author that has been described as “Mommy porn” and “Twilight” for grown-ups, has electrified women across the country, who have spread the word like gospel on Facebook pages, at school functions and in spin classes.

2. The discussion of the sex itself, usually either winking references to the book’s naughty pictures of nekkid girls—in handcuffs! or patronizing dismissals on the grounds that the books aren’t depicting authentic hard-core kink. Here’s Newsweek:

To a certain, I guess, rather large, population, it has a semipornographic glamour, a dangerous frisson of boundary crossing, but at the same time is delivering reassuringly safe, old-fashioned romantic roles. Reading Fifty Shades of Grey is no more risqué or rebellious or disturbing than, say, shopping for a pair of black boots or an arty asymmetrical dress at Barneys.

3. Appalled indignation at the book’s anti-feminist relationship dynamics. Typical example: “Women Falling For Fifty Shades Of Degradation” from The Courant, or "Shades of Red" in The Huffington Post.

4. And finally, endless, ENDLESS complaints about how horrible the writing is. Here’s the Tribune:

The book is classified as erotic fiction, where I am sure the word ‘erotic’ is used in the loosest sense of the word. If erotic passages are meant to induce an almost impossible combination of disbelief, cringing and inadvertent hilarity then, by all means, Fifty Shades of Grey is the most erotic novel ever written. Frankly, until now, I did not think it was possible to wince, laugh, and grind my teeth at same time.

Here’s Vulture on the "Thinking Woman's Guide To Fifty Shades of Grey":

So even though I'm late to the phenomenon, I felt compelled to pick it up. After reading it, there are just a few things I don't understand. Namely, how it's possible that anybody is turned on by this.

I'm sorry. I know, it's soft porn, and it's not there to better us. But the advantage of erotic fiction over a DVD of I Can't Believe I Ate the Whole Team is that books will always at least FEEL more high-minded than movies.

I'm not going to spend more time on the fundamental problem with assuming that millions of women who liked FSOG somehow can't think, but the Vulture example is helpful in that the writer explicitly states what is obviously true of all of the reviews: that the critic would never have read the book if it hadn’t become the focus of a media storm. A lot of them admit to forcing themselves to finish it. The other thing they all have in common is that none of them read contemporary romance or erotica—why else would they pepper their reviews with references to Philip Roth, Harold Robbins, Danielle Steel, or Lolita? (Fanny Hill? Seriously WTF!). They know nothing at all about it.

None of these reactions are surprising when you ask a critic who spends his or her life writing scintillating essays assessing the latest candidates for the Booker Prize to read Fifty Shades of Grey. But they expose the fallacy that expertise in contemporary literary fiction somehow confers competence to review any contemporary novel. Discussing an influential work of genre fiction requires at a bare minimum familiarity with that genre. I would also argue that it requires a basic appreciation of that genre, including the capacity to enjoy works in it. Here is a critic from the London Review of Books:

When it comes to erotic writing, the more explicit it gets – the more heaving, the more panting – the more I want to laugh. Erotic writing is said to have a noble pedigree: the goings-on in Ovid, the whipping in Sade, the bare-arsed wrestling in Lawrence, the garter-snapping in Anaïs Nin, the wife-swapping in Updike, the arcs of semen hither and yon. But it’s so much sexier when people don’t have sex on the page.

Do I have to point out the inherent limitations of a critic attempting to assess the significance of FSOG who admits in the first paragraph that he does not find written descriptions of sex to be the least arousing?

Ultimately, my problem is not really with the critics, who are just stating their opinions. But I cannot let the journals themselves off the hook. Why on earth can’t the Times farm that review out to someone who reads hundreds of erotic novels, and preferably dozens of fan-fics also, who is familiar with the conventions, politics, levels of sexual intensity, anything at all about this genre?

Please be clear: we do not see this in other aspects of popular culture reviewing. The New York Times does not send their opera guy who can’t stand Rap to review Jay-Z. My generation (X) does not respect lines between high- and low-brow culture. We watch Jersey Shore and then write about it for the Times Magazine. We have “experts” on Manga and Anime and X-Box games who are capable of writing lucid, engaging, and persuasively authoritative essays on specific examples. (I will discuss in another essay why I think why organs like the Times are guilty of this staggering incompetence with erotica when they would never be guilty of it with Rap.)

I am not trying with this to defend FSOG. But as I said in Part 1 of this series, if you wish to understand changes in the publishing industry, you need to make sense of what is happening in romance and erotica. You need critics of the genre—thoughtful, articulate, knowledgeable readers who are familiar with its conventions and thus capable of evaluating specific examples. The problem is that editors and literary critics who are already dismissive of the genre will have to face the uncomfortable fact that these potential critics are first and foremost fans—this is true of Manga and it’s true of erotica. Reading through the reactions to FSOG, it will be a huge step for many of them to admit that such critical, intelligent reader/fans of erotica can even exist.

Originally posted on my blog: http://liliafordromance.blogspot.com/2013/11/fifty-shades-of-boneheaded-or-wtf-is.html

5

5

The Difficulties of Consent: A rambling blog post

So today I got to thinking about non-con and dub-con, which I love to read and to write. And guess what? I'm not going to apologise for that. I like exploring the blurry lines and the grey areas and all the nasty dark little corners in the human psyche. Just because.

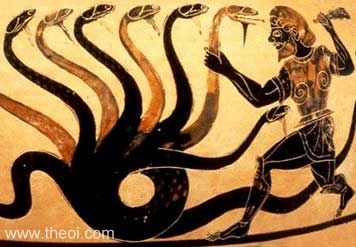

Goodreads Spawns Depraved Tentacle Monsters! Yippee!

Introduction

This series explores how the recent censorship episodes at Goodreads and booksellers in England represent symptoms of the larger upheavals roiling the publishing world. In particular I am looking how they each relate to what I will call ‘emerging genres,’ genres whose standards and conventions, critical reception, distribution and a host of other aspects are being actively negotiated and contested by a community of “stakeholders”: authors, fans, reviewers, critics, publishers, etc. Since I am both a writer and heavy reader of erotica and its subgenre, M/M romance, I will use those as my primary lens for analyzing the implications of these scandals.

As I said in my first piece, erotica’s connection to the British scandal is self-evident. The connection to Goodreads is less direct, but I think in the end more important. There is nothing unexpected that booksellers stung by criticism that they sell pornography would react impulsively by attempting to purge it from their shelves. The Goodreads episode was not concerned with erotica at all, and superficially the types of material censored seem quite narrow in scope, but in fact its implications for those who care about erotica or any emerging genre are far more sinister, and unlike the British scandal there was nothing inevitable about it.

Controversy at Goodreads

With longstanding, ugly quarrels it can be very difficult for outsiders to get past the he said/she said aspects. The conflict that spawned this debacle is polarized enough by now that any pretense to impartiality is impossible, and I am not going to spend time arguing "my side." Though I have had no role whatsoever in this quarrel, I do think the reviewers have the right of it. (For those interested in immersing themselves in the details, I refer you to an excellent series of posts on the blog Soapboxing as well as the book Off-Topic, discussed below.)

For the purposes of my own argument, it is enough to know that a very vitriolic conflict between authors and readers over negative reviews mostly of YA books has been escalating for more than a year, drawing negative press and the kind of attention social networking sites most fear.

It is not chance that this conflict erupted over YA, which along with erotica is one of the genres that has been most popular with self-publishing authors. One of the fundamental facts of life for those of us who self-publish is that reader reviews and word-of-mouth are crucial.

Now authors getting a wee verklempt about bad reviews is nothing new (though brownies help—as do tequila shots). What is new is how crucial reader reviews are to sales, and how visible they are. The moment a Goodreads review is posted, it is accessible worldwide by the site's 20 million users. As if that weren't enough, booksellers like Kobo (and now Amazon on certain Kindles) also post Goodreads reviews on the book page for buyers to see.

Goodreads' Author Guidelines strongly warn authors never to respond to negative reviews, but authors don’t always realize or don’t care, and some have gone after “bully” reviewers for sabotaging their careers, even resorting to tactics like "doxing," tracking down and posting real names and addresses for hostile adversaries to see. Readers on Goodreads began keeping track of these authors and slapping with the “Badly Behaving Author” label, which can be very damaging since the tag tends to go viral on the site, and many Goodreads users make a point of never buying any book by a BBA.

Goodreads' Response

Given the publicity and acrimony surrounding these fights and their threat to the reputation and actual functioning of Goodreads, it was not surprising that the site’s management felt they had to intervene—which they did on September 20 with the following announcement:

[Goodreads will] Delete content focused on author behavior. We have had a policy of removing reviews that were created primarily to talk about author behavior from the community book page. Once removed, these reviews would remain on the member’s profile. Starting today, we will now delete these entirely from the site. We will also delete shelves and lists of books on Goodreads that are focused on author behavior.

There are a lot of reasons this was a problem. The policy itself as worded is nonsensical. As people have pointed out, does the prohibition on discussing “author behavior” apply to reviews of Mein Kampf? Does their insistence that "books should stand on their own merit" mean we cannot discuss Orson Scott Card’s very public anti-gay statements when reviewing Ender’s Game? (For an excellent survey of critical approaches that emphasize “author behavior,” see Emma Sea's Why Goodreads New Review Rules Are Censorship.)

Far more baffling was that Goodreads would come down so decidedly on the authors’ side, when according to their own guidelines any author involved in a conflict with a reviewer is de facto guilty of inappropriate conduct. Because management has said nothing about their thinking, users have been left the fear the worst: that the decision represents the first stage in a larger shift by Goodreads, which is now owned by Amazon, away from reviewing and the free exchange of ideas towards a bottom-line prioritizing of selling books and advertising.

Whether those fears are grounded or not, it simply staggers that a site devoted to book lovers could conclude that the best way to quell rancor and controversy was through censorship of one side. It is no surprise that the result was an explosion of anger and protests that has drawn in users who would never be at risk of having a shelf or review deleted, and risks yet more attention from the media. And here’s where I’d like to back up my claim in the previous essay on how management’s decision represents a serious failure to understand the mentality of the site’s users.

A Community of Stakeholders

As far as the economics of publishing today goes, there are two crucial types of reader: the first is the old-style consumer whose book purchases are based on the best-seller lists or recommendations by mass-media organs of varying degrees of prestige. It is no stretch to say that these buyers pay the salaries of traditional establishment publishing.

Then there is our second type of reader, the one who is driving the new publishing paradigm. This reader is a passionate and voracious consumer of an emerging genre dominated by self- and indie publishing. Because there are no professional reviews, and often no agents, editors, or publishers to decide on a book’s merits, that role falls to the readers. Many of them read 100, 200, 500 books a year in their genre. They are not just fans, but taste-makers, and ultimately authorities—because there aren’t any others. Most heavy readers of erotica and M/M fall into this category—as do many of Goodreads’ most active reviewers.

When you first join Goodreads, the site appears to work like Facebook—indeed, it invites you again and again to duplicate your FB friend list on the site. That suggests the creators conceived of it as a place for actual, real-world friends to exchange book recs and post the occasional review. And for our first type of reader, that is probably all that is needed or wanted.

But for the second type of reader, Goodreads serves as the primary meeting place for what I earlier termed the stakeholders of an emerging genre. To take a conspicuous example, the M/M Romance reader group, one of the largest on the site with more than 12,000 members, justly advertises itself as “The #1 resource on the web for M/M fiction.” Beyond providing dozens of fora for readers to talk books or meet authors, the group also organizes innovative publishing events including an incredibly popular one where readers suggest a story line which any author is free to take up. Readers get hundreds of free stories that they had a hand in creating, while authors get exposure, a chance to experiment, and the good will of the community. The M/M group organizers are powerful players in their own right, and work tirelessly along with bloggers, authors, and readers to help develop this genre.

For these users, Goodreads is infinitely more than Facebook-with-books-instead-of-pictures-of-the-kids. It is a professional and creative space, and the key meeting place for their community. For them, the autocratic and boneheaded nature of management’s decision is deeply disturbing, especially in the light of Amazon’s acquisition of the site. Management’s move seems geared towards casting users more in the passive role of our first type of reader. It is not paranoid to say that this familiar type of reader is infinitely preferred by the traditional publishing establishment. It is the second type who is revolutionizing the industry, rendering obsolete all the old axioms on who matters, what succeeds, and how you make money.

Goodreads has itself in part to thank that this second type of reader has found her voice. After the site’s managers announced the new policy on September 20, users immediately organized protests, dubbed hydra reviews, which went viral. When those were censored, the protesters put together a collection of essays, Off Topic: The Story of an Internet Revolt, which was published on November 3 with no restrictions on distribution. In the four days since it went live, hundreds of users have shelved or reviewed the book, and a write-in campaign has started to nominate the book for the Goodreads Choice Award.

Whether this new reader will continue to find a home on Goodreads is impossible to know. What is clear is that she will never again be satisfied with the role of passive consumer of other people’s taste.

From: http://liliafordromance.blogspot.com/2013/11/goodreads-spawns-depraved-tentacle.html

16

16

1

1